I recently finished reading a book called ‘The Bronte Cabinet: three lives in nine objects’ by Deborah Lutz. It discussed the lives of the Bronte sisters through items of theirs that they made and owned throughout their lives. It also quotes from their novels, talks about their friends, family and the experiences other Victorian women had at the time.

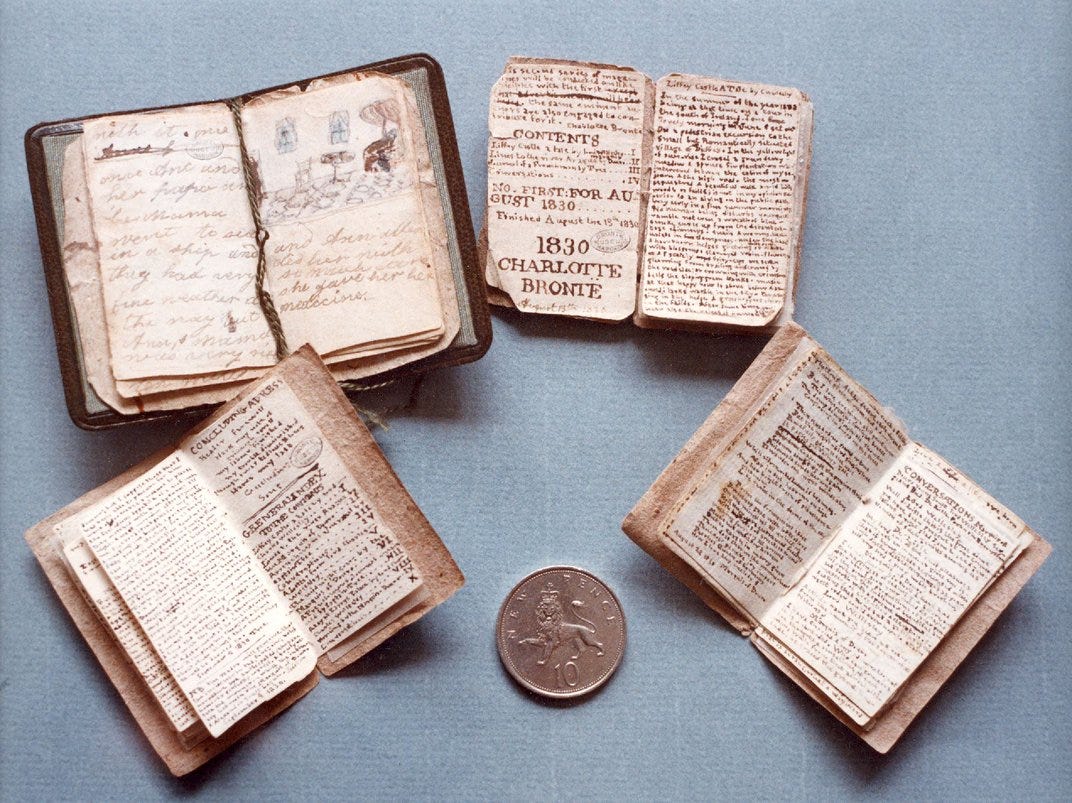

Lutz was able to examine the tiny handmade books the Bronte’s made as children, and she describes almost reverently how they feel and how they smell. In a later chapter she discusses how, after their deaths, people longed to own anything that had belonged to the famous sisters. People wrote letters to their father Patrick begging for a signature or a piece of their handwriting. In the book ‘My Life in Middlemarch’, Rebecca Mead, similarly, is able to examine a notebook of George Eliot’s, and she writes of the power of handling it, the smell of it, and the thoughts and feelings it evokes.

Reading both these accounts has pulled up a lot of thoughts and feelings, ranging from the power authors and their stories have on us, to the power that objects have, and what we can learn from them.

Years before I read either ‘Jane Eyre’ or ‘Wuthering Heights’ (I confess I haven’t read any of the other novels, and none of Anne Bronte’s novels either), I would watch the 1983 version of ‘Jane Eyre’ with my mother and older siblings. As a child growing up in the 1980s, it wasn’t as easy to get ahold of British shows as it is these days. We would watch ‘Jane Eyre’, the 1970’s version of ‘Poldark’, the 1983 ‘Jamaica Inn’ with Jane Seymour, and the 1970 ‘Wuthering Heights’ with Timothy Dalton (who also played Mr. Rochester in the 1983 ‘Jane Eyre’). My mother would say, “I want to watch something dark and English” and these were our choices.

When I was nineteen, I traveled with my mother, my aunt and a friend of ours to England and Scotland, and we were able to visit the Bronte Parsonage Museum. We were able to get a bed and breakfast in the town and stay the night. In a scrapbook I kept, I wrote (apologies for my somewhat old-fashioned, flowery language!), “It’s a beautiful house — and how incredible to behold with one’s own eyes the couch where Emily Bronte died!. . . and there were so many things of theirs one could see — sewing boxes, and shoes, and even dresses! They had part of a dress of Charlotte’s that I instantly fell in love with: white with light green polka-dots.”

Seeing those things, being in the house, was important. I wrote at the time, and I still remember the sweet feeling I had being there. I was sure the girls had been happy in their parsonage home.

In retrospect, there are many things I saw on that trip that I didn’t appreciate at the time (I barely mention anything about Salisbury Cathedral), but I was moved by the Bronte house in a way that I haven’t forgotten.

Why does it matter, visiting a place where someone famous once lived? There is the idea of pilgrimage, which took hold of people’s minds almost as soon as the Bronte sisters died. Lutz discusses the old habit of religious pilgrimages and how secular pilgrimages have the same holy intensity. I know my view of famous people has been strongly altered by visiting places where they lived.

Why, too, does it matter, holding the objects that once belonged to these people? I think it’s interesting that both Rebecca Mead and Deborah Lutz mention the smell of things.

A few years ago, one of my cousins sent me some old family keepsakes: a lot of old cards, school report cards, letters, tickets, some dating as far back as the late 1800s. Among these things were the WWII ration cards of my grandparents, my aunt and uncle and my father, who was a toddler when he had his ration card. On all these paper memories, a faint, pleasant perfume lingers, probably what my grandmother used to wear. I never knew my grandmother, and I have only these remnants, and few items of clothing in order to piece together an idea of her.

While studying archaeology, I was able to handle many interesting objects, most of which were completely anonymous. I was able to touch the bones of a woman buried in the Roman town of Verulamium, and ancient carved balls that no one quite knows why they were carved, or what they were used for. In the case of the latter, in my small class, these objects held a peculiar fascination for us all. We were reluctant to let them go, they felt so good to touch.

I haven’t had the opportunity to handle something owned by a well-known author or poet, but in the encounters I’ve had, both through archaeology, and personal experience, I’ve learned that there is a sacred nature to the objects that remain from people’s lives.

An example of this that is powerful to me is when I bought a 1920s dress from an antique store when I was 17 years old. I’ve bought many old items of clothing, before and since, but for some reason, this particular dress feels different. I wore it a few times as a teenager, and every time I would handle it, I thought about the girl who’d originally owned it. Who was she? What was she like? And every time I think about the dress now, I wonder the same things. The power of person is still connected to this object.

Like the scent of things mentioned above, people’s lives and spirits, whether the person is well known or anonymous, remain with the things they had and used. These things can’t bring back the dead, or even give us an accurate story of their lives. But, like an archaeologist, it helps us piece together something intangible about them. Sometimes these objects can give us a temporary and exciting connection that we otherwise wouldn’t have, and that is the power of visiting someone’s home, handling their things, experiencing their lives through the objects they left behind.

Lots of intriguing ideas here! I’ll have to read this book!