It’s not an exaggeration to say that it was a life-changing moment. I’ve mentioned it in a couple of my previous posts here before, but I guess I really want to drive the point home.

It was either 2000 or 2001. I was eighteen years old, and like most Americans, I hadn’t learned a lot about WWI in school, and nothing about soldier-poets. So, when I went to an exhibit in the special collections area of the library at Brigham Young University, I had no idea what was about to happen.

I went with my mother, and my sister Morag. We looked at posters with pictures of young, fresh-faced soldiers, captured in black and white. We read quotes from their poems, we watched videos of British actors reciting their works.

After spending a long time going through this exhibit, I think we were all pretty overwhelmed. I wanted more. I got my hands on books of poetry: Wilfred Owen, who died one week before the war, and Siegfried Sassoon, who lived a long life. I also found two incredible compilations: A Deep Cry: Soldier-poets killed on the Western Front; and The Fierce Light: the battle of the Somme July-November 1916 Prose and Poetry, by Anne Powell. Though they are two of the most famous, I was especially impressed by Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon. I was sensitive and shy, and didn’t get out a lot as a teenager, and I was swept off my feet by these gallant, doomed young men.

In September of 2001, a mere matter of days after 9/11, I was able to travel to England and Scotland with my mother, my Aunt Dianne, and a friend of ours. In many ways, that trip was a pilgrimage to me, and I am grateful that I was able to make it when I was young and impressionable, and full of awe.

We visited Craiglockhart outside Edinburgh, which was a hospital during WWI, and where Siegfried Sassoon was sent after he made a public declaration against the war. There he met Wilfred Owen, who was convalescing, and they became friends, and helped each other with their poetry. We also visited Sassoon’s grave in a beautiful village called Mells (which had it’s own WWI memorial to a local boy, a large equestrian statue within the church). We also visited Shrewsbury Abbey, where there is a modern memorial to Wilfred Owen, and where we walked by one of the houses he’d lived in before the war.

St. Andrew’s Church in Mells, as well as the war memorial, also had a carved panel of a peacock by Pre-Raphaelite artist Edward Burne-Jones. Both the church and the churchyard had a lovely, peaceful feeling. Giant, lush trees towered over the low, sleeping stones. My mother suggested we sing a hymn to Sassoon, and we chose ‘Lead Kindly Light’, and when we sang the words,

And with the morn those angel faces smile,

Which I have loved long since, and lost awhile!

we thought of the soldiers that he served with and for, and how they had haunted him his whole life. A few years after this, I bought a copy of Sassoon’s printed diaries from 1915-1917, and he actually mentions the above hymn, though not in a complimentary way:

So much for God. He is a cruel buffoon, who skulks somewhere at the Base with tipsy priests to serve him, and lead the chorus of Hymns Ancient and Modern. ‘O God our hope in ages past!’ ‘Rock of ages, cleft for me.’ ‘Lead, Kindly Light’ — O the stupid cynicism of it! I can see God among the pine-trees where birds are flitting and chirping. And spring will rush across the country in April with tidings of beauty. But spring in this cursed ‘year of victory’ will be but a green flag waving a signal for devilish slaughter to begin… February 22nd 1917

But something else I did not know when I stood by his grave as a young woman, was that in his old age, he converted to Catholicism.

In the past few months, I have been revisiting Sassoon, and he feels like an old friend. It’s been a long time since I read his memoirs, though I do still read his poetry. Reading his letters and journal entries as an older man has been very interesting and illuminating.

The book I have been reading is: ‘Siegfried Sassoon: Poet’s Pilgrimage’ assembled with an introduction by D. Felicitas Corrigan. Corrigan was a nun and friend of Sassoon’s. She goes throughout his life and uses his own words to show his state of mind and spirit, and the ideas and thoughts he wrestled with. His letters, poems and journal entries after his conversion to Catholicism are remarkable. His spirit is uplifted, he is no longer tormented, and it is beautiful to see. In a letter to Felicitas Corrigan, dated 29 March 1960, he writes,

I have often asked my poor old self how much I would have been prepared to give up by becoming a Catholic. And the answer is always the same. Everything asked of me.

Though I own a few biographies about Sassoon, I have yet to read them, so I don’t have a very detailed idea of his life between the war-time years he wrote about, and his later life. He had many relationships during the 1920s, with Ivor Novello, Glen Byam Shaw, Stephen Tennant (whose oldest brother was one of those soldier-poets who died in the war), and others. His relationship with Stephen was the most important among his homosexual love affairs, and lasted six years before the latter ended it. He met Hester Gatty shortly after this, and in 1933 they married. She was twenty years younger than himself. They had one son, George, but ended up separating in 1945. He mentions her in his letters at Christmas-time, it sounds like they spent holidays together, and she took care of him after he had a bad fall a few years before his death.

As he grew older, he disliked being remembered as only a war poet frozen in time. He thought of himself primarily as a Poet, in a universal way. He often marvels at the way his poems would just come to him, and shared this in his letters to his friends. In a letter from 26 March 1966, he writes to Felicitas Corrigan:

I just go on being told that I am a war poet, when all I want is to be told that I am only a pilgrim and a stranger on earth, utterly dependent on the idea of God’s providence to my spiritual being.

I like the idea that my husband Nick and I might have been great friends of his. I think he and Nick would agree on a lot of things, especially music. I can see us all sitting together and talking for hours, especially as I learned in his letters and diaries that people would come and visit him and he would graciously welcome them into his home and spend time with them. It inspired this poem, with which I will wrap up this long and rambling post:

Old Friends (to Siegfried Sassoon)

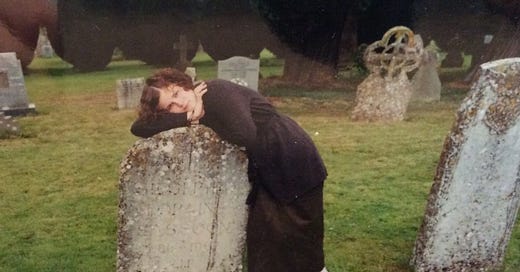

When I was nineteen, traveling through Britain with my mother, we found Your quiet grave, the lichen kissing the stone As though you had been resting much longer Than thirty-four years. I draped myself over your headstone, I knelt at your feet, and we sang a Hymn to your memory, and thought of You, haunted by the dead when we sang Of angel faces. Now, twenty-three years have passed, And as I read your words again, Your opinions of fellow-poets, your Worries about your soul, I wish that we could visit you, My husband and I, Sit with you in your cloistered Library, and discuss the troubled role Of every Artist-Prophet.

Oh, Mairi! Thanks for sharing your thoughts and feelings about Sassoon, and for a deeper glimpse into his life and thoughts. I'm surprised to realize he was still alive when I was born--and it was comforting to be reminded of his conversion to Catholicism, and the comfort that brought him.

Yes, Yes, you have done it rarely this time! You have breathed life into a rare and treasured past, in our lives as well as his. You have given facts and insights I did not know before. What joy was that innocent sympathy and love, that exploring of Self against such a backdrop of horror. Thank you a dozen times over, anew!