I recently took part in

’s wonderful virtual book club. We read ‘Winters in the World’ by Eleanor Parker, and at the end, we had a Zoom chat together and with the author. The whole experience was delightful.One of the participants talked about visiting Bath in England (which I myself have never been to) and how the tour of the Roman ruins was very formal. I thought of the Roman ruins Nick and I were able to visit this past March, and how they were open to the elements, one in a park, one along a busy road. How did they come to be there?

I’ll begin with the story of the Antonine Wall. I had grown up hearing about Hadrian’s Wall, probably because my mother and oldest sister had visited the place when I was about four years old, so I saw the pictures of their trip, and heard the stories of their adventures. But it wasn’t until I was at Uni that I’d even heard of the Antonine Wall.

After coming to Britain in AD 122, the emperor Hadrian ordered a wall to be built along the northernmost frontier of their empire in Britain. The wall was dotted with forts along the way, and it stretched from the Solway Firth in the west to Wallsend on the east coast.

It was Antoninus Pius, Hadrian’s successor, who wanted to reach even further north, and temporarily abandoned Hadrian’s Wall to construct a new wall, not of stone, but of turf.

This wall was 40 miles long, with a wide, deep ditch in front of it. Like Hadrian’s wall, forts were built along the wall. It was occupied only for about twenty years before being abandoned. The Roman Army then retreated south, reoccupying Hadrian’s Wall.

When Nick and I were in Glasgow this past March, we saw a lot of artifacts excavated from the Antonine Wall, housed in the Hunterian Museum. The Roman ruins that we encountered were two bath houses! One in Bothwellhaugh, a village south of Glasgow, the other in Bearsden, just north of Glasgow, and very near the Antonine Wall.

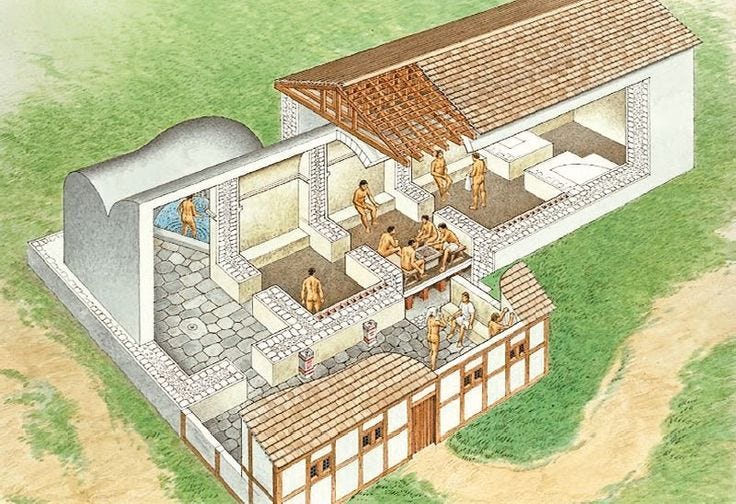

It’s fascinating to me that bath houses were important to the Roman army as they were traveling north and building fortifications. There are over twenty Roman bath house sites maintained by the English Heritage alone (there are, of course, a lot of Roman ruins in England!). They understood the benefits of bathing, and it was a priority even for soldiers on the frontier, to build these complex bathing houses with multiple rooms, and baths of varying temperatures.

The excavated ruins are open to the elements, and in March when we visited, seemed cold and uninviting. But when they were first built, they must have been comforting as well as cleansing, and an escape from the cold, rainy weather in Scotland. There were cold baths available, but many were heated with ducts beneath the floor, and must have been very nice, especially in the cold winter months.

I’m glad that we were able to visit these Roman bath houses, that we could find them and casually explore the rooms and try to imagine the time when Roman soldiers marched north into Scotland.

Love this reflection! I was the one who commented on the experience at Bath and it was indeed very different from our visit to Hadrian’s wall or even to other Roman sites I’ve been to that are more “open air”. I’m sure part of it’s because there is still a functioning spa adjacent to the Roman ruins in Bath (and I didn’t see any spas while sloshing through muddy sheepfields along Hadrian’s wall, much though I could have used one)!

Fascinating! Bring back bath houses